Single-Sided Deafness (SSD), or unilateral sensorineural hearing loss, refers to significant or total hearing loss in one ear. The hearing loss is usually permanent and may be the result of a variety of conditions including:

Acoustic Neuroma

-

Sudden deafness – can occur at any time, often for unknown reasons

-

Physical damage to the ear

-

Pressure on the hearing nerve

-

Inner ear problems including infections (viral or bacterial)

-

Diseases such as measles, mumps, meningitis

-

Disorders of the circulatory system

-

Severe Meniere's disease

-

Trauma – e.g. head injury

Head Shadow Effect

An issue which affects communication for people with SSD is the “head shadow effect." Sounds that originate from the side of the deaf ear fall in the shadow of the head.

Vowel sounds which have longer wavelengths may still travel from the deaf side to the hearing side, but consonants which have a shorter wavelength and carry the most meaning for speech and conversation, don’t do as well in terms of making their way from the deaf ear around the head to the hearing ear.

This can cause a great deal of frustration for the individual with SSD especially when trying to communicate in the presence of background noise.

Another issue for people with SSD is directionality. Directionality (or sound localization) is an important aspect of managing communication and environmental cues. When you’re unable to hear out of one ear, crossing the street, cycling and jogging can all become difficult and even dangerous. Unexpected communication challenges arise in situations such as:

-

Communicating in the car (deaf side facing driver)

-

Interacting in circular group meetings (can be difficult even if participants are speaking

one at a time and even worse if distance is a factor for large circular discussions)

-

Whispered communication into the deaf ear in quiet environments such as church, lectures, movies or training

All of the above situations can greatly affect day-to-day life. As a result, some people with SSD find themselves exhibiting irritability and jumpiness, have frequent headaches (due to stress), feel socially isolated and experience chronic interpersonal communication difficulties. Undetected SSD in children may even be misdiagnosed as ADHD.

CROS and BiCROS Hearing Aids

In cases of SSD, the deaf ear receives no clinical benefit from amplification. This means that no matter how loud we make things through a hearing aid, speech is not clear or usable in that ear. The other ear often has typical or regular hearing ability, but not always.

As with any hearing loss, we cannot restore the hearing once it has been lost. For SSD, there are treatments available which can restore the sensation of hearing to the deaf side. One treatment option available for SSD is a CROS or BiCROS hearing aid system.

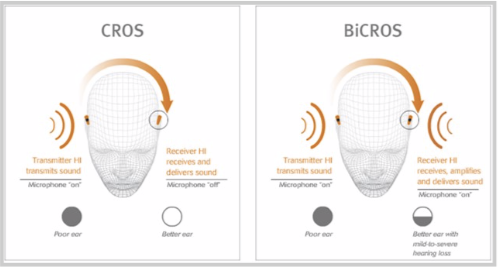

CROS hearing aids systems are worn by individuals with one deaf ear and one ear that is unaffected by hearing loss. With a CROS hearing aid system, a transmitter (which looks like a behind the ear hearing aid) is worn on the deaf ear. The transmitter’s microphone picks up sound from the deaf ear and sends it to a receiver (hearing aid) that is worn in the ear that has hearing.

BiCROS hearing aid systems are worn by individuals with hearing loss in both ears, but one ear is deaf and unaidable. In this case, a transmitter is worn on the deaf ear. The transmitter’s microphone picks up sound from the deaf ear and sends it to a receiver/hearing aid that is worn in the better ear. But as the better ear still has hearing loss, amplification is provided to that ear along with the information coming from the deaf ear.

Communication Styles

Having a hearing loss doesn’t mean you need to take a backseat in life. One important step is to understand the type of communicator you are and with the right adjustments, you’ll be on the road to a lifetime of good communication. On the most basic level, there are three kinds of communicators: Passive, Aggressive and Assertive.

Passive communicators often start out in denial about their hearing loss before comfortably sliding right into the background – not wanting to call attention to their problem or ask for help. “Passives” will avoid situations and conversations where they may need or want to participate.

“Aggressives” have no problem letting you know that they have a hearing loss or that you may need to modify some aspects of your communication. Aggressive communicators tend to dominate conversations – the more they talk, the less they must try to listen.

"Aggressives" often place blame on others during communication rather than accepting their own role and responsibility to ensure that they understand. They may even go as far as ignoring their communication partners when they don’t understand.

Unlike passives, “assertives” ask for communication help when necessary, but don’t demand it like "aggressives." Assertive communicators stand up for themselves to ensure that their needs are met. They do this through a blend of mastering effective communication strategies and advocating for themselves.

The Basics of Being an Assertive Communicator

-

Let others know that you have a hearing loss upfront.

-

Don't be afraid or embarrassed to ask for what you need.

-

Keep background noise low.

-

If you are unsure you understood, summarize what you think was said so the speaker

can confirm or explain again.

-

Face the person you're speaking with.

-

Try to keep a sense of humour.

-

Don't be too hard on yourself and give yourself a break in a quiet area to regroup.

-

If you're too tired or distracted for a conversation, ask to postpone.

Things to Consider About the Environment

-

Do your best to have a conversation in a place with good lighting, so you can see the speaker's face, gestures and body language.

-

If you're going to a restaurant with friends or family, try to arrange a time that is not during peak dining hours. Try to sit somewhere away from noisy spots such as the server’s station or kitchen.

-

When you're with a group of people, try to position yourself in the middle of the room or group so you have visual access to most people's faces.

-

If you're joining a conversation with a group, ask for the conversation topic so you have contextual cues.

Communication Repair Strategies

-

Get your attention before starting a conversation

-

Face you when speaking

-

Repeat more slowly

-

Rephrase what he or she has said

-

Give you the keyword or subject of conversation

-

Spell a word

-

Write something down, especially important dates, times or appointments

-

Use gestures

-

Simplify or shorten the sentence

Ask for Help When You Need It!

-

Use "I" statements (e.g., “I need you to please repeat that last number”)

-

Explain why you need an adjustment

-

Be specific

-

Be polite

Canadian Hearing Society (CHS)

If you live near an office, CHS may be able to help you in the following ways:

Audiology - hearing tests, hearing aids, tinnitus help

Connect Counseling – mental health challenges

Hearing Care Counseling – In-home hearing counselling help for 55+

Employment Services – Job search activities and workplace accommodations

CART – Communication Access Real Time (CART)

Hearing Help Classes (communication strategies, hearing aid workshops)

ANAC Support Group – Toronto

Although being diagnosed with an acoustic neuroma can and often is an overwhelming experience for most people, understanding how you can make the most out of your communication options can help you cope better and stay connected to others.

Rex has been an audiologist since 1989 and is the Director of Audiology at the Canadian Hearing Society. In addition to being registered with the College of Audiologists and Speech Language Pathologists of Ontario (CASLPO), Rex is also a certified member of the American Speech Language Hearing Association (ASHA) and holds the Certificate of Clinical Competency in Audiology (CCC-A) designation.