Background

The cornea is the normally transparent, clear window of the eye. Possible sequelae of acoustic neuroma surgery include facial nerve palsy with or without corneal anesthesia, both of which can severely compromise corneal comfort and integrity required for clear vision. The facial nerve innervates closure of the eyelid and facial muscles.

With facial nerve palsy, the lower eyelid may be everted (ectropion), and the eyelids may not close completely (lagophthalmos). Since the cornea requires constant moisture and protection, facial nerve palsy may lead to corneal breakdown (keratopathy), corneal opacification and infection, with loss of vision and or discomfort ulceration. The first branch of the trigeminal nerve innervates the cornea and provides important nutritional factors and protection for the eye.

Traditional methods for corneal protection after facial nerve palsy or trigeminal anesthesia include frequent lubrication, moisture chambers, tarsorrhaphy (sewing parts of the upper and lower lid together), punctal occlusion, upper lid gold weights and springs. A newer surgical intervention to restore corneal sensation is corneal neurotization, but this procedure requires a donor graft, may require a year to work, and is not always successful.

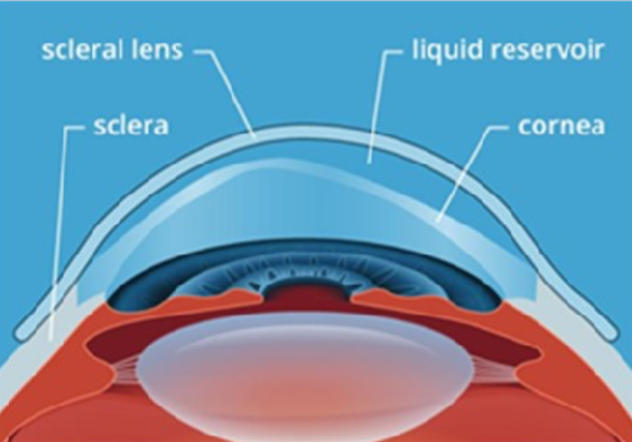

Over the last decade, an increasingly popular non-surgical method to protect the cornea in patients with facial nerve palsy with or without trigeminal anesthesia is the gas-permeable scleral contact lens (SCL). SCLs are much larger than conventional contact lenses, and rest on the less sensitive white of the eye (sclera) rather than the cornea. A saline solution fills the space between the cornea and the SCL, keeping the cornea moist. These lenses have several advantages over tarsorrhaphies, which are cosmetically unappealing and can limit peripheral vision. SCLs offer much better aesthetics than tarsorrhaphy, and can optimize vision, especially in patients with corneal scarring.

Some Canadian optometrists who belong to the Scleral Lens Education Society are found at the website: https://sclerallens.org/find-fitter/?country=Canada

Scleral Contact Lenses

All eyes are shaped uniquely, and as such SCL require customized fitting and measurements of the front of the eye. (Russell, 2016). This process is conducted by an optometrist or contact lens fitter with specialty training in SCL fitting. The initial fitting process may take an hour, and training to learn to insert and remove the SCL may take more than an hour (Woo, 2014). Patients are often dispensed lenses within weeks of the initial fitting, but completion of the custom lens may take several months to finalize.

Of note, due to the lengthy customization of SCLs, they are more costly than conventional lenses. Patients should contact their medical/vision insurance company to determine if they have benefits that may cover a portion of the cost of fitting and/or of the SCL themselves. A letter from their ophthalmologist or optometrist may be required to show proof of medical necessity.

Prior to SCL insertion, non-preserved saline is used to fill the entire lens. (see Figure) To ensure the solution does not spill out of the lens, patients must tuck in their chin while looking down usually into a mirror. One hand is used to open the eye fully and the other hand is used to insert the lens. A scleral lens suction cup (see Figure) is most commonly used to place the lens on the eye.

|

|

Scleral contact lens maximally filled with saline positioned on a “DMV” suction cup (blue).

Alternate methods include positioning the fingers into a tripod to balance and insert the lens, but patients often find this method more challenging. For patients who have great difficulty with insertion, a stand may be used so the hands are both free to hold the lids open.

If too much of the saline spills out, a bubble will form between the lens and the eye. In this case, the lens will have to be removed and re-inserted. To remove the lens, a removal plunger should be used. Patients should be proficient at putting the lenses on and taking them off prior to taking the lenses home. There are many assistive tools to facilitate insertion and removal of SCLs, including application and removal plungers, plastic rings, and stands. These can often last up to three months and can be purchased at contact lens fitter’s office. Whether an assistive device or fingers are used for application, SCL wearers should insert the lens and then release their eyelids before letting go of the lens.

When scleral contact lenses are properly cleansed and adequately maintained, they may last up to two to four years. The gas-permeable material allows for oxygen to readily pass through the lens to maintain the health of the eye. The lens protects the surface of the eye from environmental factors, hydrates the surface of the eye, while correcting irregular astigmatism caused by corneal scarring

To ensure proper long-term use of the SCL, follow-up appointments are booked every one to two weeks until completion of the fitting. Ultimately, the goal is to have a properly fitted lens that does not compromise the cornea or conjunctiva and provides optimal vision and comfort for the patient. Orange coloured eye drops (fluorescein) are often used to examine the presence and quality of the tear film between the lens and the eye.

The amount of time a patient can wear the SCL varies from patient to patient. Typically, patients with facial nerve palsy are encouraged to wear the SCL during all waking hours to protect the cornea and ocular surface. All contact lenses including SCL should not be worn at night to decrease the risk of corneal infection. In patients with facial nerve weakness, taping the lids closed, nighttime lubricating ointment and moisture chambers are advisable alternatives. If patients have an upper lid gold weight, the head of the bed should be raised to help the lids close at night.

Corneal infections are a potential risk with SCL, but the risk is minimized with good lens and hand hygiene. In a large study of over 84,000 patients who were fitted for SCLs, there were only 70 cases of reported infected corneas. Wearing contacts overnight (even gas permeable lenses) can lead to the eye being starved of oxygen. Other complications include corneal swelling, new vessel growth in the eye, conjunctival redness, fogging, and dryness of the lens during the day.

In summary, SCLs are non-surgical options in acoustic neuroma patients who have corneal exposure and/or loss of corneal sensation. SCL can help protect and heal the ocular surface, recover vision, and reduce pain for patients with facial nerve palsy. However, SCL needs to be worn appropriately and checked regularly to avoid corneal infection or other ocular surface compromises.

References

DeLoss, K. S., Kaz Soong, H. & Hood, C. T. (2019). Complications of contact lenses. Trobe, J. & Givens, J. ed. UpToDate. Waltham, MA: UpToDate Inc. https://www.uptodate.com (Accessed June 29, 2019).

Fadel, D. & Toabe, M. (2018). Scleral Lens Issues and Complications Related to Handling, Care Compliance. Journal of Contact Lens Research and Science, 2(2), 1-13. DOI 10.22374/jclrs.v2i2.24

Griffin, G., Fey, A. & Azizzadeh, B. (2017). Facial Nerve Palsy. In A. Fey and P. J. Dolman (Eds.), Diseases and Disorders of the Orbit and Ocular Adnexa. Retrieved from Elsevier ClinicalKey.

Lasby, A. (2016). The Scleral Lens Industry: Where are we Headed? Canadian Journal of Optometry, 78(1), 32-35. Retrieved from https://opto.ca/sites/default/files/resources/ documents/cjo_contact_lens_supp.pdf

Michaud, L. & Liao, J. (2016). Scleral Lens Troubleshooting Q&A. Canadian Journal of Optometry, 78(1), 25-31. Retrieved from https://opto.ca/sites/default/files/resources/ documents/cjo_contact_lens_supp.pdf

Russell, B. (2016). Visual Rehabilitation with Contact Lenses for Irregular Corneal Astigmatism. Canadian Journal of Optometry, 78(1), 4-17. Retrieved from https://opto.ca/sites/default/ files/resources/ documents/ cjo_contact_lens_supp.pdf

Scleral Lens Education Society. (2018). Patient FAQs. Retrieved from https://sclerallens.org/for-patients/patient-faqs/

Weyns, M., Koppen, C. & Tassignon, M. J. (2013). Scleral Contact Lenses as an Alternative to Tarsorrhaphy for the Long-Term Management of Combined Exposure and Neurotrophic Keratopathy. Cornea, 32(3), 359-361. DOI:10.1097/ICO.0b013e31825fed01

Zaki, V. (2015). A non-surgical approach to the management of exposure keratitis due to facial palsy by using mini-scleral lenses. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/ articles/PMC5312998/

Woo, S. L. (2014). 10 Dos and Don’ts of Scleral Lenses. Retrieved from https://www.reviewofcontactlenses.com/article/10-dos-and-donts-of-scleral-lenses

Edsel Ing MD, FRCSC, MPH is Associate Professor of Ophthalmology, University of Toronto and is the full-time preceptor of the oculoplastics, strabismus and neuro-ophthalmology fellow at Michael Garron Hospital. He is a member of the American Society of Oculoplastic and Reconstructive Surgery, the Canadian Oculoplastic Surgery society, the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, the North American Neuro-ophthalmology Society, and the Canadian and American ophthalmology societies. He has written more than 60 clinical papers and given more than 100 lectures. His special interests include eyelid surgery, eyelid tumours, orbital surgery and tumours, Graves ophthalmopathy, eye muscle realignment surgery (strabismus), and Bells palsy.

Vishakha Thakrar BSc, OD, FAAO, is an Optometrist and Contact Lens Fellow, Vaughan Family Vision Care. Dr. Thakrar has worked in optometry clinics in both Canada and the United States. She held the role of Director of Contact Lens Service at the Cole Eye Institute, Cleveland Clinic Foundation. She also participated in research activities in collaboration with the Department of Ophthalmology. In recent years, Dr. Thakrar has served as a contributing editor for the journals Contact Lens Spectrum and Eye Care Review and has written many articles on various optometric topics. She also speaks in the United States and Canada on contact lenses and eye diseases. Dr. Thakrar has received contact lens awards from Johnson and Johnson Vision Care, CIBA Vision, the GP Lens Institute and the College of Optometrists in Vision Development.

Anastasia Faggioni, BScN, is a Medical Student at Northern Ontario School of Medicine and participates as a Local Exchange Officer on the school’s Global Health Committee.